Economic Returns to Social Capital at the Global Level: A Trillion-Dollar Policy Framework for Institutional Reform, Anti-Corruption, and Sustainable Growth

Research Article, 2026,1,10[1]  Economic Returns to Social Capital at the Global Level: A Trillion-Dollar Policy Framework for Institutional Reform, Anti-Corruption, and Sustainable Growth

Economic Returns to Social Capital at the Global Level: A Trillion-Dollar Policy Framework for Institutional Reform, Anti-Corruption, and Sustainable Growth

Author: Steven H. Kim, MinKit Institute, United States

|

Received: 23.09.2025 |

Accepted: 24.01.2026 |

Abstract

Social capital has increasingly been recognized as a critical determinant of long-term economic performance, institutional effectiveness, and sustainable development. While conventional growth models emphasize physical capital accumulation, labor productivity, and technological innovation, they often underestimate the economic returns generated by trust-based institutions, transparent governance, and cooperative social norms. This paper examines the macroeconomic implications of social capital through a policy-oriented analytical framework, arguing that investments in institutional integrity and anti-corruption reforms constitute a high-return global growth strategy. Drawing on cross-country corruption surveys and historical evidence from post–World War II reconstruction—particularly the Marshall Plan—the study demonstrates that financial assistance alone is insufficient to achieve durable economic growth. Instead, the most significant gains arise when external support is paired with structural reforms that enhance market coordination, reduce rent-seeking behavior, and strengthen public trust. The analysis highlights corruption as a systemic constraint that undermines social capital by distorting incentives, eroding institutional credibility, and suppressing productive investment. The paper advances the concept of a global social capital agenda, proposing that coordinated investments in governance reform, rule of law, and institutional transparency could yield economic returns comparable to, or exceeding, those of traditional fiscal stimulus programs. By framing social capital as a scalable and measurable policy asset, the study contributes to contemporary debates on development finance, economic governance, and global growth strategies. The findings suggest that a trillion-dollar commitment to social capital reform represents not a cost, but a transformative investment in global economic resilience.

Keywords: Social capital; Economic growth; Institutional quality; Corruption; Public policy; Governance reform; Development economics

Citation in APA 7: Kim, Steven, H. (2026). Economic Returns to Social Capital at the Global Level: A Trillion-Dollar Policy Framework for Institutional Reform, Anti-Corruption, and Sustainable Growth. Bank and Policy, 6(1), 120–128.

Introduction

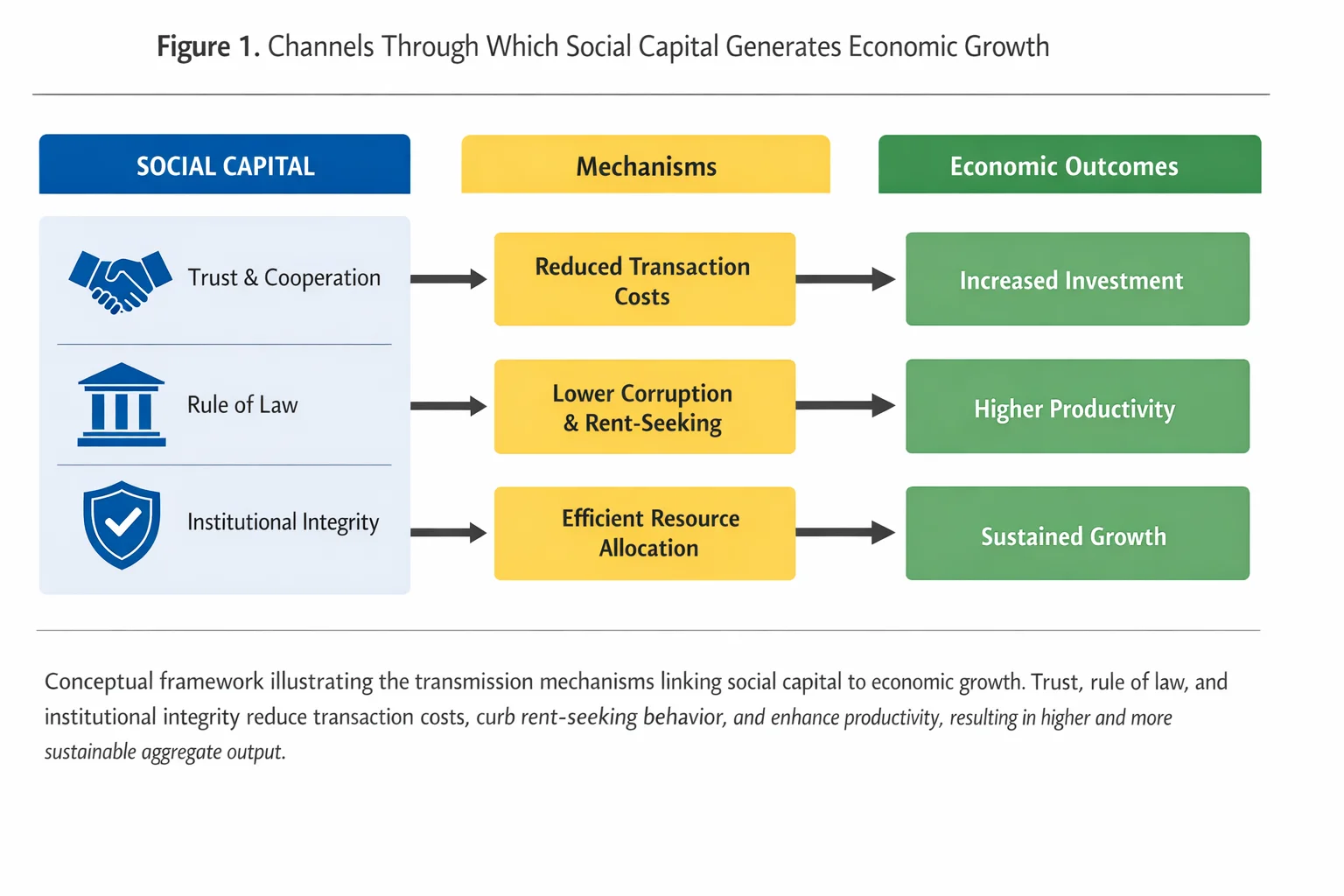

Economic prosperity is fundamentally contingent upon a society’s ability to expand aggregate productive capacity rather than merely redistribute existing output among competing groups. When economic actors concentrate on enlarging the total economic pie, collective welfare increases; conversely, when they engage in zero-sum struggles over distribution, the result is often stagnation or decline. This distinction is deeply intertwined with the concept of social capital, understood as the stock of trust, norms, networks, and institutional reliability that facilitates cooperation and coordination for mutual benefit.

The degree to which individuals and institutions adopt benign, cooperative behaviors as opposed to predatory or rent-seeking strategies reflects the overall quality of social capital within a society. Weak social capital encourages opportunistic behavior, regulatory capture, and resource misallocation, while strong social capital fosters innovation, productive investment, and long-term growth. Importantly, policies that appear to protect domestic interests through artificial restrictions often erode social capital by privileging narrow groups at the expense of society as a whole.

A classic illustration is the imposition of import quotas on consumer goods such as automobiles, textiles, food products, or leisure services. For example, restricting sugar imports into an industrialized country artificially suppresses domestic supply, driving prices upward while reducing consumption. Although such policies may benefit a small group of protected producers, they impose diffuse costs on consumers and downstream industries. In this sense, protectionist measures do not merely redistribute wealth; they destroy economic value by shrinking total welfare. This dynamic underscores the broader argument of this paper: sustainable growth requires institutional arrangements that expand cooperation, trust, and productive capacity rather than incentivize conflict and extraction.

- Corruption as a Structural Constraint on Growth

Among the most corrosive forces undermining social capital and economic performance is corruption, commonly defined as the abuse of public authority for private gain. Corruption distorts incentives, weakens institutional credibility, discourages investment, and erodes public trust in both markets and governments. From a macroeconomic perspective, corruption functions as a hidden tax on productive activity while simultaneously reallocating resources toward unproductive rent-seeking.

Empirical evidence illustrates the magnitude of this problem. A global survey encompassing over 114,000 respondents across 107 countries revealed that 27 percent of individuals reported paying at least one bribe within a twelve-month period when interacting with public institutions. Even more strikingly, 54 percent of respondents believed that their governments were largely or entirely controlled by elites pursuing private interests rather than the public good. These perceptions are not merely subjective; they translate directly into reduced compliance, lower tax morale, and diminished civic engagement.

Predictably, high-income economies tend to occupy the lower end of corruption indices. In countries such as Australia, Denmark, Finland, and Japan, fewer than one percent of respondents reported paying bribes in the preceding year. The United Kingdom recorded approximately five percent, while the United States stood at seven percent. By contrast, countries plagued by chronic corruption—many located in parts of Africa and the Middle East—exhibited dramatically higher rates, with figures reaching 74 percent in Yemen and 84 percent in Sierra Leone.

However, income alone does not guarantee institutional integrity. France, for example, presents a revealing anomaly: despite its advanced economy, survey respondents rated its business environment as more corruption-prone than the global average, including several lower-income countries such as Rwanda, Bangladesh, Albania, and Cambodia. This observation highlights a crucial point: institutional quality and social capital are not automatic byproducts of wealth, but outcomes of deliberate policy choices, governance structures, and cultural norms (Transparency International, 2013).

- Historical Lessons: Reconstruction, Institutions, and Social Capital

History provides powerful evidence of how large-scale institutional reform combined with external support can rapidly restore economic vitality. The post–World War II reconstruction of Europe stands as one of the most instructive examples. In the immediate aftermath of the war, the United States military assumed a central role in rebuilding devastated regions. Military engineers repaired infrastructure, while humanitarian aid programs supplied food, clothing, and medical assistance to millions of civilians.

During this early phase, local economies were buoyed by both supply-side and demand-side effects. On the supply side, foreign expertise and material resources compensated for destroyed domestic capacity. On the demand side, the presence of American military personnel—with significantly higher purchasing power than the local population—stimulated commerce in services ranging from retail and hospitality to entertainment. However, once the U.S. military and civilian contractors withdrew, many local economies experienced a sharp contraction. The sudden disappearance of external demand and logistical support exposed the fragility of domestic economic structures.

The resulting crisis triggered intense political pressure for rapid solutions. In countries such as Germany, widespread unemployment, housing shortages, and food insecurity fueled growing support for centralized economic planning. Yet centralized systems proved ill-equipped to manage the complexity of postwar economies, which required millions of decentralized decisions regarding production, pricing, and resource allocation. As economic theory and experience demonstrate, price signals in competitive markets provide far more effective coordination mechanisms than bureaucratic directives (Kim, 1990).

- The Marshall Plan and Institutional Transformation

Recognizing these challenges, the United States launched the European Recovery Program, widely known as the Marshall Plan. Between 1948 and 1951, the program delivered approximately $13 billion in aid—equivalent to roughly $130 billion in 2015 dollars—to eighteen European countries, including the United Kingdom, France, and West Germany. While the financial scale of the program was significant, it represented only a fraction of total U.S. assistance during and immediately after the war. Prior to the Marshall Plan, Western Europe had already received over $9 billion in U.S. transfers, and wartime grants and credits exceeded $48 billion by mid-1945 (U.S. Department of State, 1949).

The true impact of the Marshall Plan, however, lay not merely in financial transfers but in its conditionality. Recipient countries were required to dismantle extensive systems of price controls, rationing schemes, and trade barriers. These reforms curtailed the expansion of state-led allocation mechanisms and reasserted the primacy of market-based coordination. In effect, the program catalyzed a structural shift away from ad hoc socialism toward market institutions, reinforcing property rights, competition, and cross-border trade.

The results were striking. In the British and American occupation zones of Germany, industrial production stood at only 51 percent of its 1936 level in mid-1948. Within six months, output surged to 78 percent, and by 1958 it had increased more than fourfold relative to early 1948. After adjusting for population growth, industrial output per capita more than tripled. In contrast, East Germany—operating under centralized planning—experienced prolonged stagnation over the same period (Henderson, 2008).

These outcomes confirm that the primary contribution of the Marshall Plan was institutional rather than financial. By reinforcing social capital through trust, predictable rules, and decentralized decision-making, the program laid the foundation for sustained economic growth (De Long & Eichengreen, 1991).

Policy Implications: A Global Social Capital Agenda

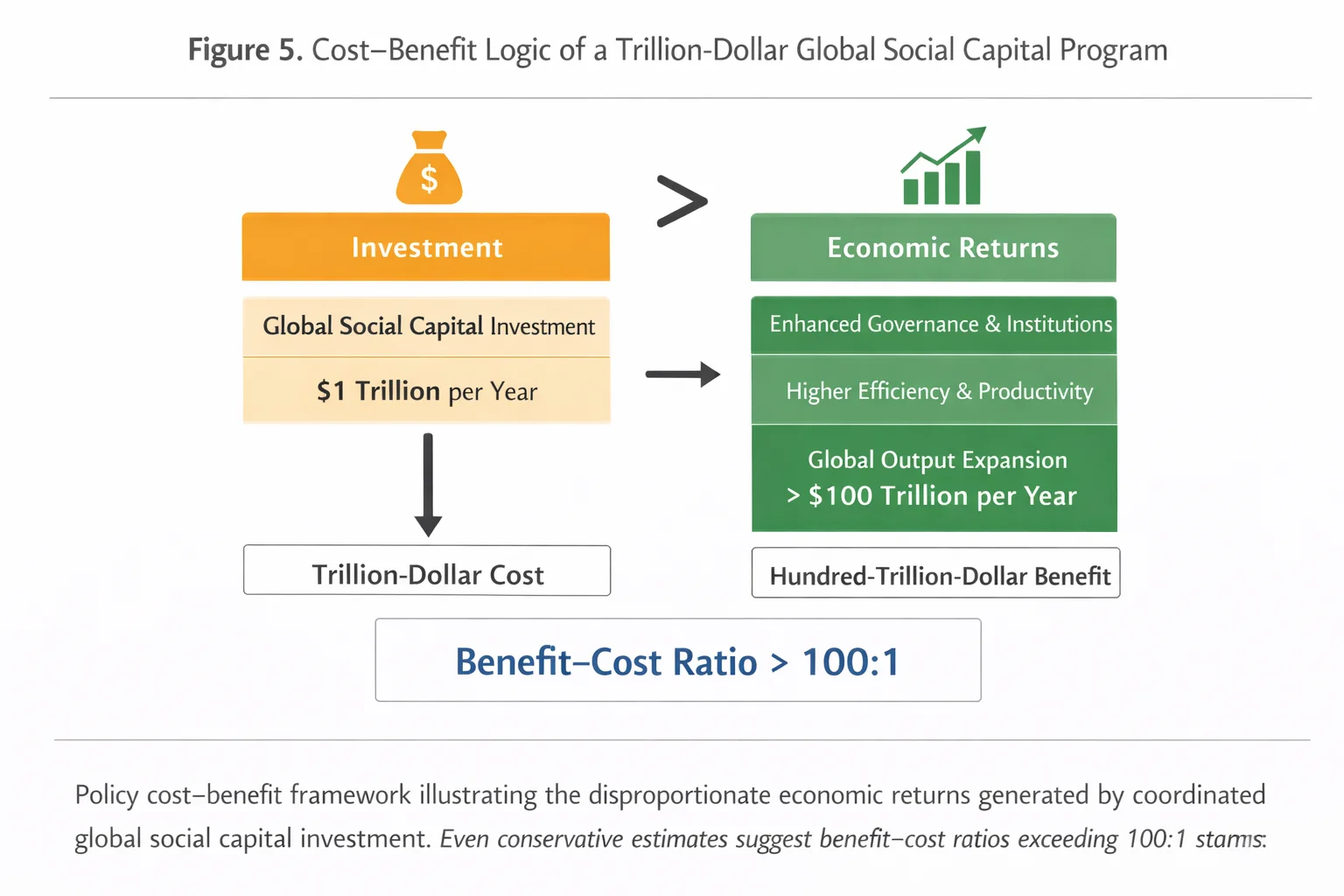

The historical experience of postwar reconstruction offers valuable lessons for contemporary policy. Large-scale financial assistance alone is insufficient to generate lasting growth unless it is accompanied by institutional reforms that strengthen social capital. A modern “trillion-dollar agenda” for global development should therefore prioritize:

- Anti-corruption frameworks and transparent governance,

- Legal and regulatory systems that protect property rights and contracts,

- Market-based coordination supported by credible public institutions,

- Investment in trust-building mechanisms across societies and borders.

Such an agenda would not merely redistribute resources but expand global productive capacity, yielding returns far exceeding the initial investment.

- Intergenerational Sacrifice and the Political Economy of Postwar Aid

The numerical estimates presented in earlier sections capture only a partial representation of the magnitude of the sacrifices undertaken by the American public during the post–World War II reconstruction period. A more meaningful assessment requires situating foreign assistance within the broader context of national income and economic capacity at the time the Marshall Plan was initiated.

When the European Recovery Program formally commenced in July 1948, the nominal gross domestic product (GDP) of the United States stood at approximately USD 279.5 billion annually. The Marshall Plan’s allocation of USD 13 billion was not an isolated intervention but rather followed substantial postwar transfers that exceeded USD 9 billion between 1945 and 1948. Taken together, U.S. transfers to Europe between 1945 and 1951 amounted to approximately USD 22 billion, equivalent to 7.9 percent of U.S. GDP at the onset of the Plan (U.S. Department of Commerce, 1949).

To place this figure in contemporary perspective, U.S. national income in late 2015 totaled USD 18.1 trillion in nominal terms (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 2016). An equivalent commitment of 7.9 percent today would correspond to roughly USD 1.43 trillion, underscoring the extraordinary scale of postwar generosity relative to national means. Importantly, this figure understates the broader scope of U.S. assistance, which extended geographically to East Asia—including Japan—and temporally through successor programs such as the Mutual Security Act (1951–1961) and the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961.

During the mid-1950s, when the Mutual Security Program was fully operational, U.S. GDP had risen to approximately USD 430.9 billion, while annual aid disbursements of USD 7.5 billion represented nearly 1.7 percent of national income (U.S. Department of Commerce, 1949). Notably, these transfers were concentrated on a limited geographic area—primarily Western Europe—at a time when the United States itself remained a country of relatively modest income by modern standards.

In 1948, the U.S. population stood at 146.6 million, yielding per capita output of roughly USD 1,907, equivalent to about USD 18,746 in 2015 dollars after adjusting for inflation (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2016). By contemporary benchmarks, this level of income would place the United States around 90th globally, comparable to middle-income economies such as Bulgaria or Gabon (Central Intelligence Agency [CIA], 2016a).

Despite these constraints, American citizens—through both public policy and private initiative—channeled a substantial share of their limited income toward international reconstruction. This intergenerational sacrifice highlights a critical normative lesson: affluence is not a prerequisite for solidarity, and today’s far wealthier economies possess ample capacity to undertake a similarly ambitious global investment strategy.

Figure 1. Channels Through Which Social Capital Generates Economic Growth (Original, belongs to author).

- Limitations of Conventional Aid and the Migration Fallacy

Since the late twentieth century, foreign aid policy in advanced economies has increasingly shifted toward a passive, transfer-based model, emphasizing financial assistance while neglecting institutional and cultural reform. This approach has produced uneven and frequently disappointing outcomes, despite the allocation of trillions of dollars in development assistance since the 1950s (Blackwill & Harris, 2016).

In response to persistent underdevelopment, some policy advocates have proposed large-scale migration as an alternative mechanism for global income convergence. Influential economic estimates suggest that removing all barriers to labor mobility could increase global output by 50 to 150 percent, depending on assumptions regarding migrant productivity (Clemens, 2011). While such figures are theoretically provocative, they rely on assumptions that lack institutional and political realism.

Empirical migration models often assume that migrants would achieve between one-quarter and one-half of host-country productivity levels. Aggregated estimates suggest that up to 75 percent of the population in developing regions could migrate under fully liberalized regimes, potentially raising global income by approximately 95 percent (Clemens, 2011). However, such scenarios abstract entirely from social cohesion, institutional capacity, political stability, and absorptive limits.

In practice, even modest migration flows—amounting to a few percentage points of the host population annually—have been associated with labor market distortions, fiscal pressures, social fragmentation, and political backlash in advanced economies. Far from doubling global output, unrestricted mass migration would likely precipitate economic dislocation and institutional breakdown, harming both migrants and host societies (Kim, 2016).

- Methodological Framework: Estimating Returns to Social Capital

Given the impracticality of mass migration as a development strategy, this study adopts an alternative methodological lens: estimating the potential gains from systematic investment in global social capital. Social capital is operationalized here as the combination of institutional trust, rule of law, governance quality, and civic norms that enhance productivity and economic coordination.

Rather than reallocating populations, this approach seeks to elevate productivity in situ, enabling entire societies to converge toward higher income equilibria. Unlike migration-based models, which benefit only a subset of the population, social capital investments generate inclusive gains, improving outcomes for 100 percent of residents in reforming countries.

The methodological benchmark employed in this section is comparative productivity. By examining output per capita in advanced economies and extrapolating attainable productivity levels under improved institutional conditions, it becomes possible to estimate the upper bound of potential global gains.

Figure 2. Cost–Benefit Logic of a Trillion-Dollar Global Social Capital Program (original, belongs to author)

- Global Productivity Gains from Institutional Convergence

In 2015, U.S. GDP totaled approximately USD 17.95 trillion, yielding output per capita of USD 55,800. Adjusted for population growth and trend productivity, per capita output was projected to exceed USD 56,700 in 2016 (CIA, 2016b). During the same period, the European Union recorded purchasing-power-adjusted output of USD 19.18 trillion, with per capita income averaging USD 37,800, reflecting structural heterogeneity across member states.

Globally, gross world product (GWP) measured at purchasing power parity reached approximately USD 114.2 trillion in 2015, corresponding to average per capita output of USD 15,700. Assuming continuation of recent trends, global growth averaged around 3.2 percent annually (CIA, 2016b).

To illustrate the scale of unrealized potential, consider a counterfactual scenario in which global productivity converges to contemporary U.S. levels. Multiplying U.S. per capita output by the global population of 7.32 billion yields a hypothetical world output of approximately USD 415 trillion. By comparison, projected actual output for 2016 was approximately USD 117.6 trillion, implying a productivity multiple of 3.6.

The implied output gap—nearly USD 300 trillion annually—represents the theoretical upper bound of gains from comprehensive social capital enhancement. While such convergence cannot occur rapidly, even partial realization would dwarf the returns of traditional aid or trade liberalization initiatives.

Importantly, this estimate is conservative. The United States itself operates below its productive frontier due to regulatory distortions, policy uncertainty, and crisis-era interventions that inhibited market adjustment following the 2008 financial collapse. These constraints suggest that global convergence toward an improved institutional benchmark, rather than the current U.S. model, could yield even greater long-term gains (Blackwill & Harris, 2016).

Table 1. Scale of U.S. Foreign Assistance Relative to National Income (1945–1955)

|

Period |

Program / Aid Channel |

Annual or Cumulative Aid (USD, nominal) |

U.S. GDP at Time (USD, nominal) |

Aid as % of GDP |

|

1945–1948 |

Immediate postwar grants and credits |

>9 billion (cumulative) |

279.5 billion (1948) |

3.2% |

|

1948–1951 |

Marshall Plan (ERP) |

13 billion (cumulative) |

279.5 billion (1948) |

4.7% |

|

1945–1951 |

Total postwar transfers to Europe |

22 billion |

279.5 billion |

7.9% |

|

1951–1961 |

Mutual Security Program |

~7.5 billion per year |

430.9 billion (1955) |

1.7% |

Source: U.S. Department of Commerce (1949); Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (2016).

Interpretation: Postwar U.S. foreign assistance represented an exceptionally high share of national income, exceeding contemporary aid norms by a wide margin.

Table 2. U.S. Economic Capacity at the Launch of the Marshall Plan (Historical vs. Modern Perspective)

|

Indicator |

1948 Value |

Inflation-Adjusted / Comparative Value |

|

Nominal GDP |

USD 279.5 billion |

— |

|

Population |

146.6 million |

— |

|

GDP per capita (nominal) |

USD 1,907 |

USD 18,746 (2015 dollars) |

|

Global income rank (2015 comparison) |

— |

≈ 90th globally |

|

Comparable economies (2015) |

— |

Bulgaria, Gabon |

Source: U.S. Census Bureau (2000); U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2016); CIA (2016a).

Interpretation: The United States undertook unprecedented foreign aid commitments despite income levels comparable to today’s middle-income economies.

Table 3. Limitations of Migration-Based Growth Scenarios

|

Study Scenario |

Share of Population Migrating |

Estimated Increase in Global Output |

Key Assumptions |

|

Scenario A |

73.6% |

+96.5% |

Partial productivity convergence |

|

Scenario B |

53.0% |

+67.0% |

Moderate institutional neutrality |

|

Scenario C |

>99% |

+122.0% |

Near-frictionless absorption |

Source: Clemens (2011).

Interpretation: Migration-based growth estimates rely on unrealistic assumptions regarding institutional capacity, social cohesion, and political feasibility.

Table 4. Comparative Policy Approaches to Global Income Expansion

|

Policy Strategy |

Population Benefiting |

Institutional Risk |

Political Feasibility |

Long-Term Sustainability |

|

Trade liberalization |

Partial |

Low |

High |

Moderate |

|

Mass migration |

Minority |

Very high |

Low |

Low |

|

Financial aid (passive) |

Limited |

High |

Moderate |

Low |

|

Social capital investment |

Entire population |

Low |

High |

High |

Source: Author’s synthesis based on Kim (2016) and Blackwill & Harris (2016).

Interpretation: Investment in social capital dominates alternative strategies in inclusiveness and sustainability.

Table 5. Global Productivity Benchmarks (2015–2016)

|

Economy / Region |

GDP (PPP, USD trillion) |

GDP per capita (USD) |

Average Growth Rate |

|

United States |

17.95 |

55,800 |

2.4% |

|

European Union |

19.18 |

37,800 |

1.2% |

|

World (aggregate) |

114.2 |

15,700 |

3.2% |

Source: CIA World Factbook (2016b).

Interpretation: Significant productivity gaps persist between advanced economies and the global average.

Table 6. Hypothetical Global Output under Institutional Convergence

|

Scenario |

Output per Capita (USD) |

Global Population (bn) |

Total Output (USD trillion) |

|

Actual World Output (2016) |

15,700 |

7.32 |

117.6 |

|

U.S.-level productivity |

56,700 |

7.32 |

415.0 |

|

Potential Output Gain |

— |

— |

+297.4 |

Source: CIA (2016b); author calculations.

Interpretation: Institutional convergence via social capital enhancement could theoretically triple global output over the long term.

Table 7. Cost–Benefit Comparison: Social Capital Investment vs. Output Gains

|

Item |

Estimated Value |

|

Annual global social capital investment |

USD 1 trillion |

|

Share of U.S. + EU GDP |

~2% |

|

Potential long-run annual output gain |

>USD 100 trillion |

|

Benefit–cost ratio |

>100:1 |

Source: Author estimates based on GDP and productivity benchmarks.

Interpretation: Even conservative estimates suggest extraordinarily high economic returns to coordinated social capital investment.

- Present Value of Long-Term Productivity Gains from Social Capital Investment

Enhancements in social capital generate economic returns that persist over time rather than producing a one-off increase in output. Consequently, the appropriate analytical framework is not static cost–benefit comparison, but intertemporal valuation, where future productivity gains are discounted to their present value.

As demonstrated in preceding sections, a hypothetical convergence of global productivity toward contemporary U.S. levels would raise annual world output by approximately USD 297.4 trillion (in purchasing power terms). Because such gains would recur annually once institutional convergence is achieved, they constitute a perpetual stream of benefits. Applying a conservative capitalization factor of 25—consistent with long-run social discounting in macroeconomic analysis—yields a gross present value of approximately USD 7.44 quadrillion.

However, institutional transformation does not occur instantaneously. The diffusion of social capital, encompassing governance reform, trust formation, and cultural adaptation, unfolds gradually. To reflect this reality, the analysis assumes a 20-year transition period, during which productivity improvements accumulate progressively rather than appearing immediately.

Historical experience supports the plausibility of robust medium-term growth during institutional modernization. Throughout the second half of the twentieth century, countries undergoing structural reform—such as Japan, South Korea, China, and later India—sustained real growth rates exceeding 6 percent annually, with episodic surges surpassing 10 percent during early modernization phases. Accordingly, this study adopts a conservative real growth assumption of 6.66 percent per annum during the transition period.

At this rate, global output after 20 years would be approximately 3.63 times its baseline level. To translate future gains into present terms, inflationary erosion must be considered. Assuming an average global inflation rate of 4 percent per annum, the present value of the post-transition productivity stream is reduced to approximately USD 3.39 quadrillion.

This estimate is intentionally conservative. Advanced economies have experienced average inflation closer to 2 percent, which would imply a present value closer to USD 5.0 quadrillion. Nevertheless, to avoid overstating the case, the lower valuation of USD 3.39 quadrillion is retained as the benchmark for subsequent analysis.

- Results: Cost–Benefit Analysis of a Global Social Capital Program

The quantitative results strongly support the economic feasibility of a coordinated global investment in social capital. Suppose that the United States and Europe jointly commit USD 1 trillion per year for 20 years to finance institutional reform, governance capacity-building, civic education, and anti-corruption initiatives worldwide. The nominal expenditure would amount to USD 20 trillion.

Because these expenditures occur over time rather than upfront, the appropriate measure is their present value. Discounting the stream of annual investments at a 4 percent real interest rate yields a present value of approximately USD 13.6 trillion.

When juxtaposed against the estimated present value of future productivity gains (USD 3.39 quadrillion), the implied benefit–cost ratio exceeds 249:1. In other words, each dollar invested today generates hundreds of dollars in long-term economic value.

Importantly, these estimates understate the true magnitude of the benefits for several reasons:

- Population Scale Effects

In 2015, the United States accounted for only 4.4 percent of the global population, yet enjoyed per capita income more than three times the global average. Institutional convergence in countries housing the remaining 95.6 percent of the population therefore produces disproportionately large aggregate gains (CIA, 2016b). - Purchasing Power Amplification

In low-income economies, even modest productivity improvements translate into substantial real income gains due to lower baseline prices and unmet demand. - Demographic Momentum

Global population is projected to reach 9.7 billion by 2050, with nearly all growth occurring in developing regions (United Nations, 2015). Productivity improvements in these regions thus generate compounding benefits over time. - Transition-Period Gains Ignored

The analysis excludes output gains realized during the 20-year reform phase. Because early gains are discounted less heavily, their inclusion would significantly raise the present value of benefits. - Depressed Baseline Productivity in Advanced Economies

Since the Global Financial Crisis, productivity growth in advanced economies has lagged long-term trends by approximately 10 percent, owing to regulatory distortions, misallocated capital, and crisis-era interventions (Wen, 2014). Institutional reform would therefore raise not only developing-country productivity, but also restore growth potential in advanced economies.

Taken together, these factors indicate that the estimated benefit–cost ratio of 249:1 represents a lower bound rather than an optimistic projection.

- Conclusion and Policy Implications

In an era of unprecedented technological connectivity and capital mobility, persistent global poverty is not a consequence of insufficient resources or opportunity, but of institutional and cultural barriers that prevent societies from realizing their productive potential. The decisive constraint is not geography or endowments, but social capital—the stock of trust, norms, and governance structures that enable cooperation and economic coordination.

Historical experience offers compelling evidence. The post–World War II reconstruction of Europe illustrates that durable recovery was driven not merely by financial transfers, but by institutional conditionality that dismantled centralized controls, restored market signals, and rebuilt civic trust. Conversely, decades of foreign aid to countries with weak institutions have repeatedly failed to generate sustained growth, underscoring the futility of capital transfers in the absence of governance reform.

A global program aimed at expanding social capital represents a fundamentally different development strategy. Rather than relocating populations or perpetuating dependency through unconditional aid, it focuses on raising productivity where people live, benefiting entire societies rather than select groups. The economic case is overwhelming: an annual investment of USD 1 trillion for two decades, with a present value cost of less than USD 14 trillion, promises long-term benefits exceeding USD 3 quadrillion.

Beyond material gains, the dividends of social capital investment extend to political stability, social cohesion, personal dignity, and international security. Higher trust reduces conflict, stronger institutions curb corruption, and inclusive growth fosters legitimacy and peace. These non-pecuniary benefits, though difficult to monetize, further strengthen the case for action.

In sum, a coordinated global initiative to build social capital is not an act of altruism, but a strategic investment with unparalleled economic and societal returns. For policymakers seeking sustainable growth, resilience, and shared prosperity, no alternative strategy offers comparable promise.

Ethical Considerations. This study is based exclusively on secondary data sources, historical records, and previously published international surveys. No human subjects were directly involved, and no personal or sensitive data were collected or analyzed. The research adheres to principles of academic integrity, transparency, and responsible scholarship. All sources have been cited appropriately, and interpretations are presented without misrepresentation or selective omission of evidence.

Acknowledgements. The author expresses sincere appreciation to colleagues and institutional peers whose scholarly discussions and critical feedback contributed to the conceptual refinement of this work. Special acknowledgment is extended to researchers and policy analysts whose foundational studies on social capital, institutional economics, and postwar reconstruction informed the analytical framework of this paper.

Funding. This research received no external funding from public, private, or non-profit organizations. The study was conducted independently as part of the author’s ongoing research agenda on institutional economics and public policy.

Conflict of Interest. The author declares no conflict of interest related to this study. The research was carried out independently, and the conclusions expressed herein are solely those of the author and do not represent the views of any affiliated institution.

References

- Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2005). Institutions as the fundamental cause of long-run growth. In Handbook of economic growth (Vol. 1, pp. 385–472). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1574-0684(05)01006-3

- Arrow, K. J. (1972). Gifts and exchanges. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 1(4), 343–362.

- Banerjee, A. V., & Duflo, E. (2011). Poor economics. PublicAffairs.

- Barro, R. J. (1996). Democracy and growth. Journal of Economic Growth, 1(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00163340

- Benounissa, L., & Benabou, D. (2025). Developing human capital and building future skills in the age of digital transformation: Lessons from the Korean experience. Science, Education and Innovations in the Context of Modern Problems, 8(12), 494–505. https://doi.org/10.56334/sei/8.12.41

- Blackwill, R. D., & Harris, J. M. (2016). The lost art of economic statecraft. Foreign Affairs, 95(2), 127–140.

- Central Intelligence Agency. (2016a). Country comparison: GDP per capita (PPP). The World Factbook. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/

- Central Intelligence Agency. (2016b). The World Factbook. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/

- Centre for Economic Policy Research. (2015). Euro area out of recession, in unusually weak expansion. https://cepr.org/

- Clemens, M. A. (2011). Economics and emigration: Trillion-dollar bills on the sidewalk? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 25(3), 83–106. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.25.3.83

- Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, S95–S120. https://doi.org/10.1086/228943

- Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere. (2015). For 70 years, delivering lasting change. https://www.care.org/

- Dahmani, A., & Bouamama, S. (2026). The relationship between psychological capital and organizational citizenship behaviors: Evidence from Algerian higher education. Science, Education and Innovations in the Context of Modern Problems, 9(2), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.56334/sei/9.2.27

- De Long, J. B., & Eichengreen, B. (1991). The Marshall Plan (NBER Working Paper No. 3899). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w3899

- Easterly, W., & Levine, R. (2003). Tropics, germs, and crops: How endowments influence economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics, 50(1), 3–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3932(02)00200-3

- Fukuyama, F. (1995). Trust: The social virtues and the creation of prosperity. Free Press.

- Henderson, D. R. (2008). German economic miracle. Library of Economics and Liberty. https://www.econlib.org/

- Kim, S. H. (1990). Designing intelligence. Oxford University Press.

- Kim, S. H. (2012). Charade of the debt crisis. MinKit Press.

- Kim, S. H. (2016). Complex factors behind misguided policies in socioeconomics: From mass migration and persistent alienation to rampant crime and economic malaise. Journal of Economics and Social Thought, 3(3), 376–399.

- Knack, S., & Keefer, P. (1997). Does social capital have an economic payoff? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(4), 1251–1288. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355300555475

- North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press.

- Olson, M. (1982). The rise and decline of nations. Yale University Press.

- Putnam, R. D. (1993). Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton University Press.

- Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon & Schuster.

- Ritschl, A. (2012). Germany, Greece, and the Marshall Plan. Economic History Review. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0289.2012.00625.x

- Rodrik, D., Subramanian, A., & Trebbi, F. (2004). Institutions rule: The primacy of institutions over geography and integration. Journal of Economic Growth, 9(2), 131–165. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOEG.0000031425.72248.85

- Sachs, J. D. (2005). The end of poverty. Penguin Press.

- Sami, B., Fadila, A., & Saadia, K. (2026). The interconnection between authentic leadership and proactive behavior in tertiary academia. Science, Education and Innovations in the Context of Modern Problems, 9(1), 33–50. https://doi.org/10.56334/sei/9.1.3

- Stiglitz, J. E. (2002). Globalization and its discontents. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Transparency International. (2013). Global corruption barometer 2013. https://www.transparency.org/

- United Nations. (2015). World population projected to reach 9.7 billion by 2050. https://www.un.org/

- Wen, Y. (2014). Evaluating unconventional monetary policies—Why aren’t they more effective? Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Working Paper 2013-028B. https://doi.org/10.20955/wp.2013.028

- World Bank. (2017). World development report 2017: Governance and the law. https://www.worldbank.org/

- Zeynalov, A. (2025). A systematic assessment of human capital investment and intellectual property protection as strategic determinants of innovation-driven economic growth in the global knowledge economy. Science, Education and Innovations in the Context of Modern Problems, 8(12), 1455–1470. https://doi.org/10.56334/sei/8.12.122

[1] Licensed

© 2026. The Author(s).

This is an open access article under the CC BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Latest news

- 30.01.2026 The Role of Blockchain Technology in Strengthening Security, Transparency, and Trust in Banking Transactions: A Conceptual and Empirical Review of Distributed Ledger Applications in Modern Financial Systems 290 views

- 29.01.2026 Modeling Financial and Investment Support for Regional Socio-Economic Development: Challenges, Mechanisms, and Strategic Directions in Azerbaijan 90 views

- 26.11.2025 Developing Countries and Trade: Strategic Capabilities, Structural Barriers, and Systemic Constraints Shaping Central Asian Economies’ Integration into Global Value Chains (GVCs) and Regional Value Chains (RVCs) 261 views

- 26.11.2025 Cross-Cultural Determinants of Mobile Banking App Adoption: A Comparative Study of University Students in Sri Lanka and the Digital Banking Context of Bulgaria 247 views

- 24.11.2025 European Economic Integration and the Future of Uzbekistan’s State Enterprises: Strategic Reforms, Institutional Convergence, and New Opportunities for Sustainable Growth 335 views

Popular articles

- 01.02.2026 Economic Returns to Social Capital at the Global Level: A Trillion-Dollar Policy Framework for Institutional Reform, Anti-Corruption, and Sustainable Growth 89 views

- 30.01.2026 The Role of Blockchain Technology in Strengthening Security, Transparency, and Trust in Banking Transactions: A Conceptual and Empirical Review of Distributed Ledger Applications in Modern Financial Systems 290 views

- 29.01.2026 Modeling Financial and Investment Support for Regional Socio-Economic Development: Challenges, Mechanisms, and Strategic Directions in Azerbaijan 90 views

- 26.11.2025 Developing Countries and Trade: Strategic Capabilities, Structural Barriers, and Systemic Constraints Shaping Central Asian Economies’ Integration into Global Value Chains (GVCs) and Regional Value Chains (RVCs) 261 views

- 26.11.2025 Cross-Cultural Determinants of Mobile Banking App Adoption: A Comparative Study of University Students in Sri Lanka and the Digital Banking Context of Bulgaria 247 views